Published 2022

Survey

of Police Use of LPR

1. Introduction

As police innovation continues to unfold, technological advancements such as

the use of body-worn cameras and License Plate Readers (LPR) have become more

widespread. However, this increase exists alongside growing scrutiny of their

use, namely surrounding issues of privacy and public trust. LPR, in particular,

has garnered significant public attention.

Although research is sparse, there is some evidence that suggests LPR use is

effective at preventing crime.1 However, police must navigate a balance between

protecting the privacy of community members and ethical use of the technology

versus the benefits LPR provide for public safety. Thus, it is important to find

ways in which law enforcement agencies can leverage the benefits of LPR for

public safety while protecting individuals’ privacy rights and maintaining or

improving public trust.

In order to reassess and expand upon the scope of current LPR implementation,

deployment, and operational usage among law enforcement agencies throughout the

United States, the International Association of Chiefs of Police (IACP)

conducted a survey of police LPR. The survey was created with input from a group

of subject-matter experts and police practitioners drawn from the IACP’s

membership. Distributed with cooperation from the State Associations of Chiefs

of Police (SACOP) in late 2020, the survey yielded 1,237 agency respondents

in 39 states. Additionally, a focus group of a subset of the agencies

surveyed was held in 2021 with more than 40 law enforcement officers, including

department leaders. The results of the survey indicated various patterns of LPR

use, and the focus group provided clarity in interpreting those results.

Local/municipal agencies were slightly over-represented in this survey, as

were mid-sized agencies. Small agencies of less than 50 officers – which make up

most police agencies in the United States – were slightly under-represented.

Some degree of self-selection bias may be present in the agencies that chose to

participate in this survey.

2.2 LPR Use

Of the responding agencies, 40% reported that they currently

use an LPR system, while 52% reported that they had never used an LPR system

(the remaining 8% reported that they had used an LPR system in the past but were

no longer using it). This is a large increase compared to results from a

survey IACP conducted in 2009 that reported only 23% of agencies surveyed

were using LPR. Consistent with the 2009 survey, the current survey

indicated that larger agencies were more likely to use an LPR system than were

smaller agencies, although the disparity has decreased, shown in Figure 1.6 The

current survey also identified that state agencies were more likely to report

using an LPR system than were other types of agencies

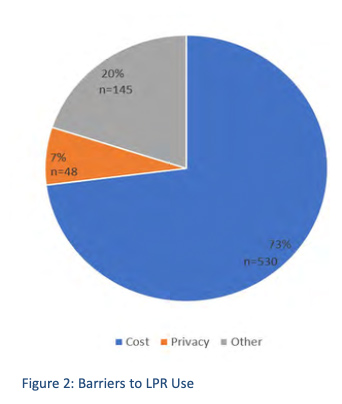

Most (86%) agencies using LPR systems reported fewer than 10

deployable units. Vehicle- mounted and stationary/fixed units were most

common, while portable units mounted on something other than a vehicle were

less common. Most (74%) agencies using an LPR had been using the LPR system for

somewhere between one and 10 years. Of the respondents who said they were not

currently using LPR systems, cost

of acquisition was the biggest reason they cited for not using the technology

(illustrated in Figure 2), and this was especially true among small agencies.

&uuid=(email))

The current survey did not ask specifically for examples of

how LPR is used. However, the focus group identified three main purposes:

investigations, crime prevention, and traffic/parking enforcement. These

results loosely align with the results of the 2009 survey which indicated

recovering stolen vehicles, traffic enforcement, and investigations as the most

common purposes of LPR.7 This topic was identified as an area for further

exploration (See Section 4).

Interestingly, most agencies using LPR systems participated in

shared usage arrangements with other agencies, though the specifics of

these arrangements varied. Approximately 80% of respondents reported sharing

data in 2020, compared to only 40% in 2009.8 These survey results led to some

obscurity in who owns the LPR systems and the data gathered from them and

who has authority to control the systems and the data gathered from them.

The focus group participants distinguished between sharing systems and sharing

data from those systems; data access to a single system was often much wider

than that of the agency who owned or controlled the system. This area is

changing and developing as technology continues to advance. Regarding access to

the databases, 69% of agencies reported that all employees needed a specific

purpose in order to access or search the LPR database. Another 22% of

respondents reported that a limited group of employees could access the

database without a specific

purpose, but other employees needed justification or could not access it at

all. Nine percent reported that no specific purpose was required to access

the database for any employee. In some cases where agencies shared systems,

agency employees could access the system, but the information returned was

limited, and additional approval was needed to obtain further data. Thus,

system-sharing or data-sharing agreements make the options for data access more

complex.

Users of the LPR system were trained in 88% of responding

agencies using LPR. Generally, training focused on technical aspects of the

system and how to use. In the other 12% of responding agencies, training was not

required to use the system. Although many survey participants indicated that

training was required to use the system, discussion in the focus group uncovered

that these trainings tended to be vendor-run, short in duration,

and only issued before initial access to the system without recurring refresher

training.

Policy Development - Data Management

3. Implications

Recent advancements in technology have allowed for

capabilities that were previously thought to be impossible. Technology has

helped make work more effective and society more efficient. Yet, the increased

reliance on technology also poses increased concerns about individuals’

privacy. In the case of LPR, police may have access to large amounts of data

with the potential to be mis-used, conflicting with Constitutional rights to

privacy. Although data from LPR are generally not considered personally

identifiable information to be protected, community- police relations have

emerged as paramount concern, making public trust imperative.

4. Conclusion

Overall, there exists large variation in how LPR policy is

set, how systems are used, and how datav is managed. In any use of technology,

it is important for agencies to communicate transparently with the community,

define specific policies and monitor adherence to them, and consider the role of

police in using technology ethically. Doing so will help strengthen

community-police relations, enhance public trust, and better enable police to do

their jobs efficiently and effectively.

|