The Strongest Press Piece

Published By a Major News Outlet

Detailing the ORC Epidemic

And in support of Senate Bill

S.936 - The INFORM Consumers Act

Every member of Congress should read the article

Send a copy to your

elected official today!

(Call to Action & Details Below Article)

Ben Dugan Works for CVS. His Job Is Battling a $45 Billion Crime Spree.

Ben Dugan, seen above in a

CVS store, the company’s top investigator, is charged with combatting

a boom in organized theft from retail stores. ZACK WITTMAN FOR THE WALL STREET

JOURNAL

Retailers are spending millions to combat

organized rings that steal from their stores in bulk and peddle goods online,

often on Amazon

Ben Dugan sat in an unmarked sedan in San Francisco’s Tenderloin neighborhood

one day last September waiting for the CVS to be robbed.

He tracked a man entering the store and watched as the thief stuffed more than

$1,000 of allergy medicine into a trash bag, walked out and did the same at two

other nearby stores, before loading them into a waiting van, Mr. Dugan recalled.

The target was no ordinary shoplifter. He was part of a network of organized

professionals, known as boosters, whom CVS had been monitoring for weeks. The

company believed the group responsible for stealing almost $50 million in

products over five years from dozens of stores in northern California. The job

for Mr. Dugan, CVS Health Corp.’s top investigator, was to stop them.

Retailers are spending millions a year to battle organized crime rings that

steal from their stores in bulk and then peddle the goods online, often on

Amazon Inc.’s retail platform, according to retail investigators,

law-enforcement officers and court documents. It is a menace that has been

supercharged by the pandemic and the rapid growth of online commerce that has

accompanied it.

“We’re trying to control it the best we can, but it’s growing every day,” said

Mr. Dugan.

The Coalition of Law

Enforcement and Retail, a trade association, which Mr. Dugan heads,

estimates that organized retail theft accounts for around $45 billion in annual

losses for retailers these days, up from $30 billion a decade ago. At CVS,

reported thefts have ballooned 30% since the pandemic began.

Mr. Dugan’s team, working with law enforcement, expects to close 73 e-commerce

cases this year involving $104 million of goods stolen from multiple retailers

and sold on Amazon. That compares with 27 cases in 2020, involving half the

total. CVS has doubled its crime team to 17 over the past two years and

purchased its own surveillance van with 360-degree cameras and a high-powered

telescope.

A clear

plastic container is used to protect CBD products at a CVS store, one of several

items

at high risk of being stolen. | PHOTO: ZACK WITTMAN FOR THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

Home Depot Inc. says the number of its investigations into these kinds

of criminal networks has grown 86% since 2016 and exceeded 400 cases last year.

The majority involved e-commerce. The company has doubled the size of its

investigative unit over the past four years, a spokeswoman said, and the unit

works alongside thousands of “asset protection specialists” stationed in stores

to spot suspected thieves.

“The digital world has become a pretty easy way to move this product,” Home

Depot Chairman and CEO Craig Menear told investors in December 2019, becoming

one of the first executives to highlight organized retail crime. “It is

literally millions and millions of dollars of multiple retailers’ goods.”

Target Corp. , Ulta Beauty Inc. and TJX Cos., which includes TJ Maxx and

Marshalls, have also bulked up their resources.

Complicating the battle is Amazon itself, which investigators and

law-enforcement officials say is one of the biggest outlets for criminal

networks, given its huge pool of potential customers and, in investigators’

view, insufficient vetting of sellers or their listings.

Retail and law-enforcement investigators say they struggle to obtain information

about potentially illicit sellers from the online giant, which generally

declines to provide information about sellers without a subpoena or other legal

action. Other online selling platforms such as eBay Inc. are more willing to

cooperate without legal intervention, investigators say.

Amazon “may be the largest unregulated pawnshop on the face of the planet,”

said Sgt. Ian Ranshaw of the Thornton, Colo., police department. “It is super

hard to deal with them.”

Amazon spokesman Alex Haurek said the company doesn’t tolerate the selling of

stolen goods and works with law enforcement and retailers to stop bad actors,

including by withholding funds, closing accounts and making law-enforcement

referrals. He said the company spent $700 million last year to combat fraud on

its platform.

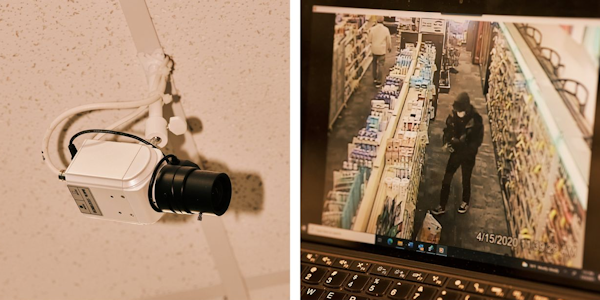

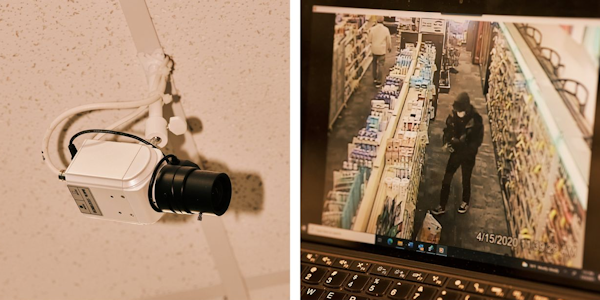

Above, various

surveillance devices that keep tabs on stores.

PHOTO: ZACK WITTMAN FOR THE WALL STREET JOURNAL (4)

Mr. Haurek said Amazon doesn’t share customers’ and sellers’ personal

information without a subpoena due to privacy concerns.

Organized retail crime has moved away from flea markets and corner stores and

onto the Internet, where criminals can move their product quickly and

anonymously. Boosters, often drug addicts targeted by crime rings, typically

sell their goods for about 5% to 10% of retail value to a street-level fence,

who then sells them to a larger-scale distributor.

Retail investigators blame changes in sentencing laws in some states for an

uptick in thefts. In California, a 2014 law downgraded the theft of less than

$950 worth of goods to a misdemeanor from a felony. Target recently reduced its

operating hours in five San Francisco stores, citing rising thefts.

&uuid=(email))

The corporate investigators charged with tackling the problem are often former

police. They tail thieves, compile investigative reports, stalk storefronts for

stolen goods and comb through trash outside suspects’ houses. They pore over

videos from stores that have been robbed and scour profiles on online

marketplaces.

Mr. Dugan rarely wears hats, after boosters said they assumed anyone wearing a

hat was a cop. (The exception, Mr. Dugan said, is Boston, where everyone wears

hats.)

Store staff are instructed not to apprehend thieves for safety reasons. Retail

investigators will sometimes let a theft unfold to help identify a fence.

Earlier this year, an e-commerce analyst on Mr. Dugan’s team who looks for

sellers hawking high-risk products such as allergy medicine or razorblades

identified an Amazon account with over $1 million in suspicious listings. It was

linked to a video store in Leominster, Mass. Local law enforcement, working

together with CVS and other retailers, arrested the owner of the video store in

May. Amazon kept the store up for at least six more weeks after the arrest.

Amazon’s Mr. Haurek said the account was closed “at the earliest appropriate

time after reconciling inventory and completing necessary documentation.”

In late 2017, CVS investigators interviewed three different shoplifters who all

said they worked for “Mr. Bob,” a man named Robert Whitley, who owned a business

in Atlanta. Mr. Dugan shared pictures of the thieves with his counterparts at

Target, Publix and Walgreens. They were getting hit by the same people,

according to investigators and case documents.

The four teams, working with the FBI and the U.S. Postal Service, took two years

to unravel the network of shoplifters who had stolen over-the-counter medicines

from hundreds of stores in nearly a dozen different states.

Mr. Whitley operated an Amazon store, Closeout Express, for about seven years

and sold $3.5 million in stolen goods on the platform, according to court

documents. In April, Mr. Whitley pleaded guilty to transporting stolen property

across state lines; his daughter pleaded guilty to conspiracy to do so. They

await sentencing. Amazon said it cooperated with the investigation.

Donald Beskin, the Whitleys’ lawyer, disputed the characterization of the case,

but declined to elaborate.

Law enforcement has become more focused on organized retail crime in recent

years. Some states have formed regional task forces devoted to the issue.

To help those efforts, Walmart sometimes gives detectives a corporate credit

card to use for undercover sting operations. In the Atlanta investigation, CVS’s

Mr. Dugan said he provided FBI agents with cases of electric toothbrush heads

and Fusion razorblades to help an agent make an undercover sale to Mr. Whitley.

Last year, Home Depot paid for more than $400 in equipment, including a GPS

tracker, to help Colorado police follow a member of a crime ring who was

transporting stolen power tools to a house 1,000 miles away in Katy, Texas.

The view

inside Steven Skarritt's house, which was stacked with allegedly stolen goods

from Home Depot.

Through his attorney, Mr. Skarritt denied wrongdoing.

The Katy house had been turned into a warehouse, complete with an elevator

moving goods between floors, where Steven Skarritt, a former painting

contractor, allegedly ran an Amazon storefront that sold almost $5 million in

stolen goods between 2018 and 2020, according to a search warrant investigators

served Amazon with in January.

The elevator was “something I’ve never seen in my career,” said Jamie Bourne, a

Home Depot organized retail crime investigator involved in the case, who was

there when law enforcement raided Mr. Skarritt’s house last October. They

recovered 55 pallets of stolen Home Depot merchandise, including power drills,

levels and vacuums.

Mr. Skarritt was charged in mid-July with first-degree felonies for money

laundering and engaging in organized criminal activity. Amazon closed his

account later in July. Amazon spokesman Mr. Haurek said it had agreed with Texas

law enforcement to temporarily keep the account open to support the

investigation.

In a recent court filing, Mr. Skarritt’s attorney, Q. Tate Williams, said there

was no direct evidence Mr. Skarritt was aware of the thefts or that any of the

stolen merchandise from Colorado was part of his inventory. “He denies and

intends to vigorously defend these charges,” Mr. Williams said.

Mr. Skarritt's house

included an elevator for moving goods between floors.

In recent years, retailers have pressed Congress to pass legislation requiring

e-commerce sites to verify details for third-party sellers and make certain

information public, making it harder for people to sell stolen goods.

Amazon, along with other online marketplaces including eBay, has lobbied against

the bill, saying such measures would invade sellers’ privacy. Mr. Haurek said

the legislation would favor large retailers at the expense of small businesses

that sell online.

“We believe the most effective way to stop fraud and abuse is for Congress and

the states to increase penalties and provide law enforcement with greater

resources,” he said.

Last year, Amazon began conducting interviews to verify seller identities, and

now does so for the “vast majority” of prospective sellers, Mr. Haurek said. The

company also requires prospective sellers to provide government-issued

identification, addresses, credit cards, bank accounts and taxpayer information.

It also makes public some seller information. The verification process last year

stopped more than six million attempts by apparent bad actors to create new

seller accounts, he said.

In last autumn’s San Francisco case, CVS investigators for weeks tracked a ring

of nearly two dozen boosters targeting their stores who were stealing up to

$39,000 a day in merchandise.

They followed the stolen goods to two units in a warehouse facility in Concord,

Calif. When investigators, working with local law enforcement, ran the address

through an online database, one business stood out: D-Luxe.

The company was owned by a man named Danny Drago—known to boosters as “Daniel

the Medicine Man” for the types of products he bought—and his wife, Michelle

Fowler. A website for the company said it did business with Amazon’s “Top Rated

Sellers.”

On Sept. 10, CVS’s Mr. Dugan asked Amazon for more details on its relationship

with D-Luxe. Amazon refused, saying it would respond only to a subpoena from law

enforcement.

When the San Mateo sheriff’s department served a search warrant to banks

associated with Mr. Drago and Ms. Fowler on Sept. 28, investigators realized the

Drago enterprise was bigger than they had thought, according to people close to

the investigation. The district attorney’s office, through a court order, froze

the accounts.

Investigators believed Mr. Drago and Ms. Fowler were involved in a nearly $30

million operation, the people close to the investigation said. Between 2017 and

2019, they operated at least two Amazon storefronts, the people said. They also

sold to at least three other sellers on Amazon, one of the people said. CVS

estimates the operation was selling $5 million a year in stolen goods on Amazon

or to other Amazon sellers in recent years.

A haul of

stolen goods seized by authorities in San Mateo, Calif., just one small part of

the estimated

$45 billion in annual losses for retailers from theft.

Amazon suspended at least one of the accounts in 2019 and both are now closed.

“The account was blocked after we suspected the seller could be listing

improperly obtained product, and the seller couldn't produce valid invoices,”

Amazon’s Mr. Haurek said.

Mr. Haurek declined to comment on CVS’s estimate of the Drago operation’s sales.

He said the company worked closely with law enforcement to help break up an

additional ring Mr. Drago had supplied, including closing four seller accounts.

When Amazon suspects a seller may be hawking goods it purchased from a retail

crime ring, it requests invoices, purchase orders or other proofs of sourcing,

he added.

The bank accounts indicated that Mr. Drago and Ms. Fowler also operated a

smaller eBay account, the people said. An eBay spokeswoman said stolen goods

aren’t tolerated on the site and that the company is committed to cooperating

with law enforcement and retailers.

Law-enforcement officers served Amazon and eBay with search warrants seeking

records for its accounts.

Amazon provided correspondence with Mr. Drago regarding complaints about his

suspended account, but didn’t hand over financial details of transactions or

internal notes about suspicious activities, despite repeated requests by law

enforcement, a person close to the investigation said.

Amazon provided “extensive information,” Mr. Haurek said, but didn’t provide

sales data because the warrant and follow-up requests didn’t explicitly request

it.

Mr. Dugan holds up a foil-lined bag used to evade a CVS alarm system in a

Daytona Beach, Fla., store.

PHOTO: ZACK WITTMAN FOR THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

EBay was more responsive to a search warrant, handing over detailed financial

transactions for Mr. Drago’s account on its platform, said the person close to

the investigation. Before the warrant, the company had also allowed a CVS

investigator to access more than 15,000 financial transactions for the account

associated with Mr. Drago’s storefront without any legal intervention. It

subsequently shut down the account.

Days before police arrested Mr. Drago and Ms. Fowler on Sept. 30, the pair

attempted to sell $1 million of stolen merchandise to an Amazon seller,

according to a person close to the investigation. CVS investigators set up

outside the Concord warehouse saw hundreds of boxes leaving the warehouse and

alerted law enforcement and United Parcel Service Inc., which stopped the

shipment. The seller no longer appears to have a storefront on Amazon.

When police raided the warehouse and other properties associated with Mr. Drago

and Ms. Fowler on Sept. 30, they found more than $8 million in over-the-counter

medication and other products from various retailers, along with $85,000 in

cash, according to the California attorney general’s office.

Mr. Drago, Ms. Fowler and three others were charged with criminal profiteering,

money laundering, conspiracy to commit a felony, possession of stolen property

and organized retail theft. Both Mr. Drago and Ms. Fowler pleaded not guilty and

await trial. Their lawyers either didn’t respond to requests for comment or

declined to comment.

For Mr. Dugan, it was on to the next case. This week, he hired two more

investigators.

wsj.com

The INFORM Consumers Act

Buy Safe America Coalition

WSJ Article: Ben Dugan Works for CVS. His Job Is

Battling a $45 Billion Crime Spree.

Call to Action for Every LP & AP Executive

& Even the Industry's Solution Providers

Letters from you and your team & from your CEO &

Legal Council

Objective: Get You Congressional Representative & Senator to

Read The WSJ Article & Support

The INFORM Consumers Act

This WSJ article is probably one of the most thorough and well researched

articles on ORC that we've ever seen. Every elected official should read this

and especially now, given the current bill sitting dormant in the Senate

Commerce Committee. Which has not seen any movement since its reading in March.

We've

had a couple of opportunities to get some movement when Congress has focused and

was probing Amazon. And when RILA engaged them with letters and formed the

Buy Safe America

Coalition. Which gathered some great retail support.

We've

had a couple of opportunities to get some movement when Congress has focused and

was probing Amazon. And when RILA engaged them with letters and formed the

Buy Safe America

Coalition. Which gathered some great retail support.

But in order to motivate Congress, especially now with the focus on

Cybersecurity and online criminal activity, we need every executive in the

industry to get this article on your elected official's desk. And even more

importantly, you need to get your CEO and legal council to send them a letter

as well with the article attached and the Bill linked - demanding action!

Make sure you include and provide a link to the

Buy Safe America

Coalition group as well. Make sure the official has all the resources

and sees the support for the Integrity, Notification, Fairness in Online

Retail Marketplaces (INFORM) Act, otherwise referred to as:

S.936 INFORM Consumers Act.

Sponsor:

Sen. Durbin, Richard J. [D-IL] (Introduced 03/23/2021)

Committees: Senate - Commerce, Science, and Transportation

How to

Contact Your Elected Officials

●

Locate your U.S. senators' contact information.

●

Find your U.S. representative's website and contact information.

Folks, for years everyone has talked about the need for a Federal ORC law and

now we have Bill sitting in Congress that tackles the issue. But like so many

times before, Congress is dealing with issues that far out weight this issue,

speaking realistically, and if we want to get it at least to the floor for a

vote it's going to take a Herculean effort on the industry's part to get it

there. And it needs an article of this caliber and a massive lobbying

effort. Which is all of you, your teams, your solution providers, and

especially your senior management teams - your CEO's and Legal Council.

Write a template letter everyone can sign. Make the effort easy for everyone.

And include the

Buy Safe

America Coalition information.

Every Retail CEO & Chief

Legal Council Should Demand Action

It's their fiduciary responsibility

&uuid=(email))

&uuid=(email))

&uuid=(email))