2021 Storming of the

United States Capitol

The DOJ's U.S. Capital Mob Investigation

Jan 6, 2021

'One of the Largest Investigations in American History'

Number of Defendants Prosecuted & Volume of Evidence

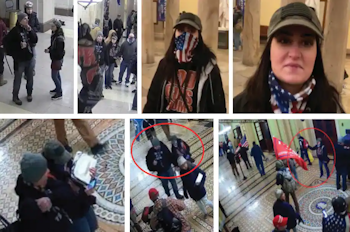

How America’s surveillance networks helped the FBI catch the Capitol mob

Federal documents detailing the attacks at the U.S. Capitol show a mix of FBI

techniques, from license plate readers to facial recognition, that helped

identify rioters. Digital rights activists say the invasive technology can

infringe on our privacy.

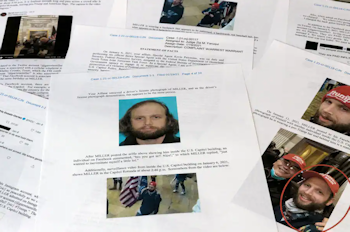

One couple's case is among the more than 1,000 pages of arrest records, FBI

affidavits and search warrants reviewed by The Washington Post detailing one

of the biggest criminal investigations in American history. More than

320 suspects have been charged in the melee that shook the nation’s capital

and left five people dead.

The federal documents provide a rare view of the ways investigators exploit the

digital fingerprints nearly everyone leaves behind in an era of pervasive

surveillance and constant online connection. They illustrate the power law

enforcement now has to hunt down suspects by studying the contours of faces, the

movements of vehicles and even conversations with friends and spouses.

The cache of federal documents lays out a sprawling mix of FBI techniques:

license plate readers that captured suspects’ cars on the way to Washington;

cell-tower location records that chronicled their movements through the Capitol

complex; facial recognition searches that matched images to suspects’ driver’s

licenses or social media profiles; and a remarkably deep catalogue of video from

surveillance systems, live streams, news reports and cameras worn by the police

who swarmed the Capitol that day.

Agents in nearly all of the FBI’s 56 field offices have executed at least 900

search warrants in all 50 states and D.C., many of them for data held by the

telecommunications and technology giants whose services underpin most people’s

digital lives. The responses supplied potentially incriminating details about

the locations, online statements and identities of hundreds of suspects in an

investigation the Justice Department called in a

court motion last month “one of the largest in American history, both in

terms of the number of defendants prosecuted and the nature and volume of the

evidence.”

&uuid=(email))

The federal documents cite evidence gleaned from virtually every major social

media service. In at least 17 cases, the federal documents cite records from

telecommunications giants AT&T, Verizon or T-Mobile, typically after serving

search warrants for a range of subscriber data, including cellphone locations.

Investigators also sent “geofence” search warrants to Google. Federal officials

filed similarly broad search warrants to Facebook, demanding the account

information associated with every live stream that day from inside the vast

complex.

License plate readers and facial recognition software together played a

documented role in helping identify suspects in nearly a dozen cases, the

federal records show.

Some cases hinged on facial recognition tips submitted to the FBI by outside

agencies. After the FBI published “be on the lookout” bulletins with suspects’

photos police forces from around the country began submitting positive

responses from far away as California. With Miami sending in 13 possible

matches.

The FBI also has been aided by the online army of self-proclaimed “sedition

hunters,” like the one who helped identify Caldwell. They scoured the Web

for clues to track down rioters and often tweeted their findings publicly in

what amounted to a crowdsourced investigation of the Capitol attack. The

citizen sleuths organized their pursuits with hashtags: Tagging one rioter "#slickback"

because ofthe way he wore his hair.

The incidents described remain allegations, with none of the cited cases having

been adjudicated yet. In most cases, suspects’ attorneys have not yet filed

defenses against charges that in many instances are only a few weeks old, court

records show.

Many cases also hinge on imperfect technology and fallible digital evidence that

could undermine prosecutors’ claims. Blurry license plate reader images,

imprecise location tracking systems, misunderstood social media posts and

misidentified facial recognition matches all could muddy an investigation or

falsely implicate an innocent person.

washingtonpost.com