This holiday season, you might want to leave home without it.

No, not American Express travelers checks, as the twist on the company's old

tagline suggests – but cold, hard cash. In an effort to cut costs and hassles, a

small but growing crop of retailers have stopped accepting the tried-and-true

paper currency.

Some restaurants in large cities began

shunning the greenback a couple of years ago, but an increasing number of

nonfood chains are going cashless at some or all of their locations or never

took bills at the brick-and mortar stores they've opened in recent years.

They include clothing retailers such as Bonobos, Indochino, Everlane and

Reformation; Amazon bookstores; Casper Mattress; Drybar hair styling; The Bar

Method fitness studios; and United and Delta airlines (both at ticket counters

and for in-flight food and drinks).

“The momentum started in the restaurant space, but we’re certainly seeing

spillover,” says Jack Forestell, chief product officer for Visa.

Visa last year awarded $10,000 to each of 50 businesses that produced videos

explaining how going cashless would benefit them.

The trend is partly rooted in the growth of credit- and debit-card transactions

and the spread of digital wallets such as Apple Pay and Google Pay. Cash isn’t

dead, but it’s no longer king. Jerry Sheldon, vice president of IHL, a retail

and hospitality consulting firm, foresees cashless restaurants and stores

comprising 40 to 50 percent of all retailers within 10 to 15 years as greenback

use continues to dwindle.

“They’re making a business decision that they

would rather make their investments in alternative forms of payment” than in

cash-handling, he says.

.png) Bonobos,

the men’s clothing chain, launched in 2007 as an online-only retailer, opening

its first brick-and-mortar stores in 2011. The company now has 59 showrooms that

largely extend its website, allowing customers to try on suits, jackets and

shirts before buying them and having them shipped to their homes.

Bonobos,

the men’s clothing chain, launched in 2007 as an online-only retailer, opening

its first brick-and-mortar stores in 2011. The company now has 59 showrooms that

largely extend its website, allowing customers to try on suits, jackets and

shirts before buying them and having them shipped to their homes.

“It feels more organic to continue the online experience” by accepting cards and

other digital payment forms, but not cash, in stores, says Emily Lewis, Bonobos'

director of guideshop operations.

And instead of having to make change and count bills, “We can … be hyperfocused

on the customer,” she says. “Finding you the right fit, getting your clothes,

helping your experience.”

On rare occasions, she says, customers try to pay in cash, but “It’s not an

issue.”

Indochino, a custom men’s clothing chain that similarly began online, says, “As

a company that was formed in the digital age, we’re prioritizing other payment

methods.”

Customers in its chief demographic, age 25 to 44, are the least likely to pay

with cash. And average orders are hundreds of dollars, making cash payments even

less likely, the company says.

Cash is losing favor

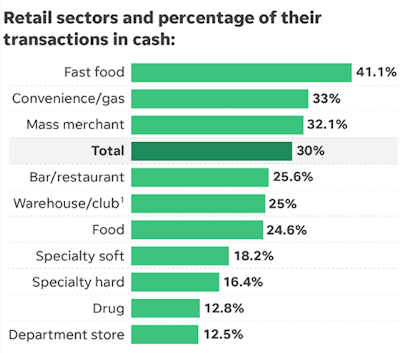

The retailers are largely following shoppers' habits. Thirty percent of all

retail transactions are in cash, down from 40 percent in 2012, according to IHL

and the Federal Reserve.

Only about a quarter of Americans made all or most of their retail purchases

with cash in 2016, down from 36 percent five years earlier, a Gallup poll shows.

Millennials are especially cash averse. Twenty-one percent of those age 23 to 34

said they make most or all of their purchases with cash, down from 39 percent

five years earlier.

“Their lives are wrapped around their little phones,” Sheldon says.

Lucas Broadway, 32, of Murfreesboro, Tennessee, says he uses his debit card “as

much as possible” – once charging 27 cents for a book of matches – allowing him

not to “worry about going to an ATM.”

Broadway “has no issue” with a cashless store and is instead irked by the

inconvenience posed by shops that take cash only to avoid paying credit-card

processing fees.

It’s no surprise that restaurants led the cashless movement, including salad

chains such as Sweetgreen and Tender Greens, Epic Burger in the Chicago area and

Petit Trois in Los Angeles. Starbucks turned one of its hometown Seattle shops

cashless.

Why? Think about holding up a line of New Yorkers with cash exchanges during the

lunch hour rush. Tender Greens says ditching bills shaves in-store orders by

about 10 seconds. The cost of cash is also steep. Bills are constantly ferried

from tables to the register and many hands touch them, making accountability a

challenge if some go missing, according to an IHL report.

Yet nonfood retailers also contend with expenses. Besides the time spent

counting bills and making change, they include ensuring registers have enough

change, running cash to the bank, bank fees, armored cars, employee theft and

robberies, the report says.

All told, such hassles cost retailers an average 9.1 percent of sales, ranging

from 4.7 percent at grocery stores to 15.5 percent at restaurants and bars, IHL

says. That compares to the 2 to 3 percent transaction fees credit-card companies

charge merchants.

Lauren Helm, owner of a Bar Method fitness studio franchise in Huntington, New

York, decided not to accept cash when she opened seven months ago to prevent

theft and better document clothing purchases. Members simply charge items to a

credit card already in the system for monthly dues.

“For some criminals, if they know we have cash, we could get robbed,” she says,

noting classes begin as early as 6 a.m. and end as late as 8 p.m. Plus, she

says, “It makes it kind of easier to spend money,” if members simply charge a

purchase, boosting sales.

Low-income shoppers could be left out

Critics

say cashless businesses hurt many lower-income Americans who don’t have bank

accounts or credit cards because they can’t maintain a minimum balance, don’t

have photo IDs or other reasons. Last year, 6.5 percent of U.S. households were

unbanked, with no members having a checking or savings account. Twenty percent

had not used mainstream credit such as a credit card or mortgage during the

prior 12 months.

Critics

say cashless businesses hurt many lower-income Americans who don’t have bank

accounts or credit cards because they can’t maintain a minimum balance, don’t

have photo IDs or other reasons. Last year, 6.5 percent of U.S. households were

unbanked, with no members having a checking or savings account. Twenty percent

had not used mainstream credit such as a credit card or mortgage during the

prior 12 months.

“It excludes people who only have access to cash,” says Christopher Peterson,

director of financial services for the Consumer Federation of America.

A minibacklash is building. Bills outlawing cashless merchants have been

introduced in Philadelphia and Washington, D.C. this year. Massachusetts has had

such a law since 1978.

“I can’t understand why (the cashless trend) is happening at all,” says Craig

Shearman, spokesman for the National Retail Federation. He says the card

processing fees merchants pay are passed to consumers, costing the average

household several hundred dollars a year.

Despite the pushback, IDC analyst Rivka Gewirtz Little predicts “significant and

continued year-over-year growth (in cashless retailers) over the next 10 years.”

Many, she says, could follow Walmart, which offers prepaid cards that don’t

require customers to have a bank account.

United, which doesn’t take cash for ticket purchases at airports or for food and

drinks in flight, supplies kiosks near ticket counters that let travelers put

cash on stored value cards.

The decision to go cashless is “part of our efforts toward creating a faster

more efficient airport experience for our customers,” United says on its

website.

This article was originally published on

usatoday.com