At height of crisis, Walgreens handled nearly 1 in 5 of the most addictive

opioids

As its own distributor & failed to report suspicious orders & prevent diversion

to the black market.

At

the height of the opioid epidemic, Walgreens handled nearly one out of every

five oxycodone and hydrocodone pills shipped to pharmacies across America.

At

the height of the opioid epidemic, Walgreens handled nearly one out of every

five oxycodone and hydrocodone pills shipped to pharmacies across America.

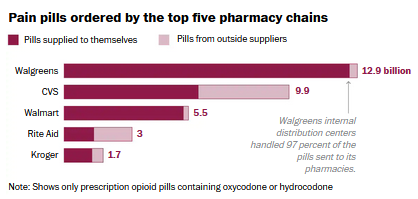

Walgreens dominated the nation’s retail opioid market from 2006 through 2012,

buying about 13 billion pills — 3 billion more than CVS, its closest competitor,

according to a Drug Enforcement Administration database of opioid shipments.

Over those years, Walgreens more than doubled its purchases of oxycodone.

The company had “runaway growth” of oxycodone sales because it continued to send

pills to stores “without limit or review,” Edward Bratton, Walgreens manager of

pharmaceutical integrity, wrote to another employee in 2013. The email is among

thousands of documents recently disclosed in a federal lawsuit that seeks to

hold Walgreens and other businesses responsible for the nation’s opioid crisis.

While most chain and independent pharmacies relied heavily on wholesalers to

supply their prescription opioids, Walgreens obtained 97 percent of its pain

pills directly from drug manufacturers, a Washington Post analysis of the data

shows. This arrangement allowed Walgreens to have more control over how many

pain pills it sent to its stores.

By acting as its own distributor, Walgreens

took on the responsibility of alerting the DEA to suspicious orders by its own

pharmacies and stopping those shipments. Instead, about 2,400 cities and

counties nationwide allege that Walgreens failed to report signs of diversion

and incentivized pharmacists with bonuses to fill more prescriptions of highly

addictive opioids.

From

2006 through 2012, Walgreens ordered 31 percent more oxycodone and hydrocodone

pills per store on average than CVS pharmacies, and 73 percent more than other

pharmacies nationwide, according to The Post’s analysis of the DEA database,

known as the Automation of Reports and Consolidated Orders System (ARCOS).

From

2006 through 2012, Walgreens ordered 31 percent more oxycodone and hydrocodone

pills per store on average than CVS pharmacies, and 73 percent more than other

pharmacies nationwide, according to The Post’s analysis of the DEA database,

known as the Automation of Reports and Consolidated Orders System (ARCOS).

When Walgreens considered surveying its pharmacies in Florida in 2011 to

identify questionable pain pill customers, a company attorney advised caution:

“If these are legitimate indicators of inappropriate prescriptions perhaps we

should consider not documenting our own potential noncompliance," according to

an email disclosed in the case.

In 2012, a drug distributor produced a report for Walgreens that flagged nearly

half of the chain’s roughly 8,000 stores for dispensing high numbers of

controlled substances, including oxycodone, court records show.

After warnings from the DEA, Walgreens agreed in 2013 to pay $80 million — a

record settlement for the agency at the time — to resolve allegations that the

company failed to sufficiently report suspicious orders and negligently allowed

controlled substances, such as oxycodone and other prescription pain

medications, to be diverted for abuse and illegal black market sales.

The large volume of pills flowing into Walgreens pharmacies made some stores

targets for crime, including armed robberies and employee theft, according to

police officials, board of pharmacy records and other published reports. In

2014, a pharmacy technician who stole about 25,000 pain pills from a Walgreens

in Missouri told state investigators that another employee gave him instructions

on how to pilfer the pills and sell them during breaks in the store bathroom and

pharmacy parking lot.

Now, Walgreens is one of the holdouts in the federal suit playing out in

Cleveland after other major distributors and drug manufacturers reached a

settlement with two Ohio counties on Oct. 21. The trial for Walgreens was

postponed until next year. CVS and other major pharmacy chains are also

defendants.

“Because Walgreens had full visibility into all dispensing related information

necessary to reveal red flags and criteria of suspicion, Walgreens might even be

viewed as more culpable due to the wealth [of] data at its complete disposal,”

the plaintiffs allege.

The company denied that it incentivized pharmacists to inappropriately fill

prescriptions and defended its practices in statements.

“Walgreens is completely unlike the wholesalers involved in the national opioid

litigation. We never sold opioid medications to pain clinics, internet

pharmacies or the ‘pill mills’ that fueled the national opioid crisis,” the

company said. “We never marketed or promoted opioid medications.”

Walgreens also said the pain pill data is “misleading” because the records are

seven years old and the chain stopped the internal distribution of controlled

substances to its pharmacies in 2014.

Employees were “incredibly diligent and careful” to ensure that pharmacies were

not involved in diversion, the company said. “We proudly stand by our pharmacy

professionals and their record of professional judgment and patient care.”

‘A directed effort’ to increase sales

Walgreens

traces its roots to 1901, when Charles Walgreen Sr. pulled together enough money

for a down payment on the pharmacy where he worked on Chicago’s South Side. He

shook up the business by adding more merchandise and making some of the drugs

himself to keep prices low.

Walgreens

traces its roots to 1901, when Charles Walgreen Sr. pulled together enough money

for a down payment on the pharmacy where he worked on Chicago’s South Side. He

shook up the business by adding more merchandise and making some of the drugs

himself to keep prices low.

His model was successful, and over the next two decades he opened about 20

stores. Today, the company operates 9,277 pharmacies in all 50 states and the

District of Columbia.

As the demand for opioids increased in the early 2000s, Walgreens expanded its

internal distribution network. The company added two facilities in Ohio and

Florida that had special security to handle controlled substances, including

oxycodone. It was an advantage over CVS, which relied entirely on outside

suppliers for the medication.

In 2006, though, regulators found problems with Walgreens’s distribution

network. In May of that year, the DEA sent the company a letter detailing

record-keeping and security deficiencies that the agency discovered during an

investigation at the Walgreens facility in Perrysburg, Ohio, according to

documents filed in the Cleveland court case.

The DEA said Walgreens had an “insufficient” system for reporting suspicious

orders of controlled substances. At the time, Walgreens identified questionable

orders by analyzing the average daily prescriptions filled by stores in groups

of 25, an internal memo shows. The DEA told the company that the size, pattern

and frequency of orders should instead be used to flag suspicious ones.

Two years later, Walgreens conducted an internal audit of its Perrysburg

facility and discovered officials there had not properly overhauled the

suspicious-order system to comply with the DEA. The audit, filed in court, noted

this was an issue at all company distribution centers and “should be addressed

to avoid potential DEA sanctions.”

In 2009, Walgreens began testing a new method at several stores that identified

suspicious orders based on order size and frequency. But an internal company

document filed in court stated that Walgreens was “capturing data but not

cutting orders.”

As the opioid crisis deepened, the DEA stepped up enforcement against drug

manufacturers, distributors and pharmacies. The agency again turned its

attention to Walgreens and threatened in a 2009 letter to revoke the

registration of a store in San Diego.

A DEA investigation found that the San Diego store on Midway Drive had filled

prescriptions issued by doctors who weren’t licensed in California. It also had

dispensed prescriptions to people the pharmacy “knew or should have known were

diverting the controlled substances,” agency enforcement records show. One

customer over seven months obtained prescriptions for hydrocodone issued by four

Florida physicians — an indication that she was “doctor-shopping” to procure

pain pills, the DEA record shows.

In April 2011, Walgreens entered into an agreement with the DEA to settle the

case. The company promised to maintain a program to detect and prevent diversion

of controlled substances from its stores across the country.

The DEA would later discover that Walgreens had been engaged in “a directed

effort to increase oxycodone sales,” agency records show. In a July 29, 2010,

email, Walgreens sent out a spreadsheet to managers ranking all Florida

pharmacies on their oxycodone dispensing with the instruction to “look at the

stores on the bottom end . . . We need to make sure we aren’t turning legitimate

scripts away.”

Meanwhile, changes in the state’s laws over the years had shifted sales of

prescription opioids from pain clinics to pharmacies. Soon the chain was

grappling with a surge of pain pill customers in Florida.

Kristine Atwell, who managed distribution of controlled substances at

Walgreens’s Jupiter facility, had emailed corporate headquarters urging that

stores justify their large volumes, including one pharmacy that ordered 3,271

bottles of oxycodone in a 40-day period.

“I don’t know how they can even house this many bottle(s) to be honest,” Atwell

wrote in early 2011 in an email previously reported on in The Post.

A few months later, Walgreens decided to review the “significant increase” in

controlled substance prescriptions in Florida, according to company emails filed

in court.

As part of its broader business initiative called “Florida Focus on Profit,”

Walgreens officials discussed surveying some of its pharmacies. The proposed

questions included, “Do pain management clinic patients come all at once or in a

steady stream?” and “Do you see an increase in pain management prescriptions on

the day the warehouse order is received?”

But Dwayne Pinon, a Walgreens attorney, warned against “documenting our own

potential noncompliance” and the questions were dropped from the survey, court

records show. Pinon, through a company spokesman, declined to comment.

Walgreens eventually renamed the survey effort “Focus on Compliance” after an

employee in an email questioned the “Focus on Profit” title.

For the first half of 2011, Walgreens accounted for 100 of the top 300

pharmacies in oxycodone purchases in Florida, and some of these company stores

bought more than double the average amount of the opioid obtained by other

pharmacies in the state, according to DEA enforcement records.

Agency investigators met with Walgreens officials that August to express

concerns about the high volume of pills. In advance of the meeting, Walgreens

sent a disc to the DEA with a file labeled “suspicious drug” orders.

“This gobbledygook is impossible to read and I stopped printing it when it

reached 2” [inches] thick,” a DEA investigator wrote in an email to her

colleagues after the meeting. “Obviously this is unacceptable.”

Days after the DEA meeting, Walgreens devised a plan to restrict a store in

Hudson, Fla., to a monthly 100 bottles of 30-milligram oxycodone, one of the

most coveted pain pills on the black market because of its potency, according to

DEA enforcement records. But the pharmacy routinely exceeded the limit,

procuring 331 bottles in September 2011, 371 bottles in October, 200 bottles in

November and 263 bottles in December, DEA enforcement records show.

Some Walgreens stores attracted so many pain pill customers that the pharmacies

had to hire security or call the police.

In Oviedo, Fla., large crowds began waiting for the Walgreens on Lockwood

Boulevard to open. Between August 2010 and November 2011, Oviedo police

responded to 17 incidents at that location, arresting 35 people for charges

related to controlled substances.

Oviedo Police Chief Jeffrey Chudnow wrote dozens of letters and contacted

Walgreens’s chairman and chief executive in March 2011 to plead for help and let

them know the pharmacy parking lots at two company stores in the city had

“become a bastion of illegal drug sales and drug use.”

Chudnow, who has since retired, told The Post that he never received a response.

The Lockwood Boulevard store doubled the number of 30-milligram oxycodone pills

it ordered from 73,300 in March 2011 to 145,400 pills in July 2011, according to

the DEA data. The Post and HD Media, which publishes the Charleston Gazette-Mail

in West Virginia, fought a year-long legal battle for access to the DEA

database.

Nationwide, the explosion in pain pills helped fuel crime. Armed robberies

spiked at independent and chain pharmacies. Some stores were repeatedly

targeted.

In Michigan, a Walgreens pharmacist purchased a gun to protect himself after the

company refused to improve security following a 2007 robbery, the pharmacist

alleged in a lawsuit. In 2011, the pharmacist shot at two masked gunmen during a

robbery attempt on an overnight shift. No one was harmed, but the pharmacist was

fired and sued Walgreens.

Later that year, an armed gunman who fled after demanding painkillers at a

Walgreens in Tennessee prompted a lockdown at nearby schools, according to

police. In Colorado Springs, robbers hit multiple Walgreens pharmacies 14 times

in 2011 and seven times in February 2012.

Gaps in the system

As pharmacy robberies made headlines, the DEA escalated its investigation of

Walgreens. The agency served warrants on six stores scattered across Florida and

the Jupiter distribution center in spring 2012.

Walgreens responded by slashing shipments of opioids to the six stores. In the

event of the DEA shutting down the Jupiter location, the chain planned to shift

distribution to outside suppliers and its Perrysburg, Ohio, facility, the same

one the DEA had cited in 2006, according to company emails filed in the court

case.

During a meeting with the DEA, Walgreens told the agency it wanted to “cooperate

and avoid litigation,” as stated in an internal company presentation from July

2012.

Walgreens

officials detailed steps the chain was taking to address the DEA’s concerns,

including updated training for pharmacists to identify suspicious prescriptions.

The company said while its suspicious-order monitoring program “did not

automatically halt suspicious orders upon identifying them, it did

systematically decrease [controlled substance] order quantities if the quantity

ordered exceeded certain thresholds.”

Walgreens

officials detailed steps the chain was taking to address the DEA’s concerns,

including updated training for pharmacists to identify suspicious prescriptions.

The company said while its suspicious-order monitoring program “did not

automatically halt suspicious orders upon identifying them, it did

systematically decrease [controlled substance] order quantities if the quantity

ordered exceeded certain thresholds.”

Later that summer, DEA investigators interviewed pharmacists at Walgreens stores

in Fort Pierce, Fla.

The DEA found that one of the pharmacists had filled at least seven oxycodone

prescriptions issued by a Miami gynecologist, ignoring warnings other employees

had left about the doctor in pharmacy records, including: “FAKE CII DO NOT FILL

ANY CII CANDY DR.”

The note referred to doctors who appeared to be writing bogus prescriptions for

substances listed on Schedule II of the Controlled Substances Act.

Questioned by the DEA about the prescriptions, the pharmacist said, “We should

not have filled them,” according to agency enforcement records.

In September 2012, the DEA employed its most severe enforcement action: Agents

padlocked a vault containing oxycodone and other controlled substances at the

Walgreens distribution center in Jupiter and later threatened to revoke the

registrations of the six pharmacies.

Walgreens responded by launching a task force and discussing ways to tighten up

oversight of opioids distributed to its stores.

When pharmacies hit limits imposed by Walgreens, they could still transfer pills

from other stores or order from outside suppliers, court records show.

Pharmacies could also find workarounds by placing special PDQ orders, meaning

“pretty darn quick,” from Walgreens internal network.

The company proposed eliminating PDQ orders for oxycodone, but Kermit Crawford,

then a top executive at Walgreens who oversaw the pharmacy business, objected to

the change.

“I was not under the impression this was a done deal. Concerned we are ‘all or

none,’ ” Crawford wrote in an Oct. 1, 2012, email disclosed in the case. “We

have to do what’s right for patients also.”

Crawford, who later became president and chief operating officer of the Rite Aid

chain, declined to comment.

At the same time, Walgreens wrestled with other gaps in the system.

In October 2012, a Walgreens pharmacy in Modesto, Calif., came under scrutiny

because it was purchasing about 17,500 pills containing hydrocodone per week,

putting the drugstore “over the corporate limit” of the number of pills it was

permitted to order, according to a company email cited in court records.

To obtain more hydrocodone, the Modesto pharmacy, on McHenry Avenue, ordered

pills from the distributor Cardinal Health, the document noted. When that set

off red flags at Cardinal Health, the store transferred opioids from nearby

Walgreens pharmacies, procuring so many pills that it led to shortages at the

other stores.

Walgreens conducted an investigation and discovered “employee pilferage” and

fired an employee, company emails filed in court show. The Modesto pharmacy also

stopped filling prescriptions from two local doctors.

Cardinal Health, which had paid a $34 million fine in 2008 to settle allegations

that it failed to report suspicious orders, declined to answer questions about

the Modesto orders and said, “We are proud of our rigorous analytics system,

including conservative, customer-specific thresholds, that we use to spot, stop,

and report to our regulators any opioid order that is suspicious.”

The McHenry Avenue Walgreens was the single largest purchaser of pain pills in

the entire Walgreens chain from 2006 through 2012, and one out of every five

oxycodone pills ordered was a 30-milligram tablet, The Post’s analysis found.

Robbers targeted the store five times for prescription opioids from 2016 through

2018, police said.

Walgreens said demand for opioids at the pharmacy was driven by hospitals,

surgery centers and other pain treatment facilities in the area.

“Walgreens thoroughly investigated concerns regarding this Modesto pharmacy

after Cardinal raised them,” Walgreens said in its statement. “We found that the

pharmacy was fully complying with all applicable internal policies and

procedures for filling prescriptions for controlled substances.”

A dramatic step

In November 2012, drug distributor Anda analyzed nearly 1.3 billion pills,

including oxycodone, handled by Walgreens. The review “flagged” 3,768 of the

chain’s pharmacies for dispensing high numbers of controlled substances in all

50 states, as well as Puerto Rico and Washington, D.C., court records show. The

report, filed with redactions, identified 226 of 253 stores in Arizona, 64 of 69

pharmacies in Oregon and all 14 stores in Maine.

Drug manufacturer Teva Pharmaceutical, which owns Anda, declined to comment.

Soon after, Walgreens launched a new division called pharmacy integrity. Tasha

Polster, who had served on the company’s task force, was tapped to lead that

effort. (Polster is not related to Judge Dan Aaron Polster, who is presiding

over the federal lawsuit).

In December 2012, Polster emailed Dan Doyle, a Walgreens finance executive, and

said without elaborating that the DEA was alleging the company’s

suspicious-order monitoring program was “inadequate.” The DEA, she wrote in the

email recently disclosed in court, was “demanding civil penalties, potentially

totaling hundreds of millions of dollars.”

Polster requested a team of a dozen people to review controlled substance orders

before Walgreens shipped the drugs to its pharmacies.

“The Company has enhanced its suspicious order monitoring program for controlled

substances in an effort to convince DEA that the proposed penalty is excessive

and that our new processes will ensure that similar incidents do not recur,”

Polster wrote.

A Walgreens spokesman said Polster and Doyle, who still work for the company,

declined to comment.

By the end of 2012, Walgreens’s orders of pain pills containing oxycodone and

hydrocodone dipped to 2.2 billion from its peak of 2.4 billion the previous

year, ARCOS data shows.

But the DEA continued to investigate. In February 2013, the agency served a

warrant and inspected the Perrysburg distribution center.

In response, Walgreens halted shipments of controlled substances from

Perrysburg. It was a dramatic move that Walgreens hoped would “eliminate any

immediate need for further DEA administrative action,” three lawyers

representing Walgreens wrote in a Feb. 20, 2013, letter to DEA officials that

was filed in the court case.

At first, Walgreens turned to Cardinal Health to distribute controlled

substances to its pharmacies. But Cardinal Health had “red flagged” 367

Walgreens stores and would not ship to them because “they are considered

suspicious,” according to internal emails between Walgreens employees.

Cardinal Health, one of the defendants that recently reached a settlement in the

national opioid litigation, did not respond to questions about its refusal to

send pills to these Walgreens pharmacies.

Walgreens soon found another distribution partner, AmerisourceBergen. In March

2013, Walgreens announced a deal that gave it an ownership stake in

AmerisourceBergen in exchange for a distribution agreement.

As the DEA investigations pressed on, Walgreens stopped filling pharmacy orders

for opioids that exceeded certain limits, according to company documents filed

in court.

This prompted pill shortages and irate customers who complained to a corporate

hotline.

In June 2013, a pharmacy manager in Greenville, N.C., emailed the pharmacy

integrity division that she had run out of oxycodone a week earlier and told

customers the drugs would arrive that day. When the pills didn’t show up, she

wrote that “luckily” she found bottles at another local Walgreens, court records

show.

“I placed a PDQ order for oxycodone . . . (one bottle will NOT be sufficient) -

please send us this order ASAP! We are losing business over this!”

The next day, Steven Mills, with the pharmacy integrity division, responded that

PDQs should be used only in “an emergency situation.”

“You have to realize the reason why we have issues with the DEA today, is due

the high amounts of Oxycodone distributions over the past 3 years,” Mills wrote

back in an email. “We had to create limits to all stores which protects the

integrity of the Pharmacist, DEA license, and the Walgreen Company as a whole.”

Half of the pain pills ordered by the Greenville store were oxycodone — nearly

twice the average of all other pharmacies across the country, according to The

Post’s analysis of DEA data from 2006 through 2012. Police said robbers targeted

the store earlier this year and stole prescription pills, including opioids.

The company said the Greenville pharmacy’s orders “were a legitimate reflection

of the demands caused by its particular location and market, and Walgreens is

unaware of any diversion of prescription pain medication at that pharmacy.”

Mills, who still works at Walgreens, declined to comment through a company

spokesman.

On June 11, 2013, the DEA announced Walgreens had agreed to pay an $80 million

civil penalty to resolve federal allegations that the pharmacy chain failed to

sufficiently report suspicious orders and that the failure was a “systematic

practice that resulted in at least tens of thousands of violations,” records

show.

In a statement at the time of the settlement, Crawford, of Walgreens’s pharmacy

division, said, “As the largest pharmacy chain in the U.S., we are fully

committed to doing our part to prevent prescription drug abuse.”

Under the agreement, Walgreens admitted that it failed to uphold its obligations

under the law and agreed to surrender its DEA registration for the Jupiter

distribution center and six stores in Florida until 2014. The settlement

addressed the claims in Florida and resolved open civil investigations into

Walgreens by U.S. attorneys in Colorado, Michigan and New York, as well as other

DEA field offices nationwide.

In Colorado, federal investigators had identified over 1,600 violations of the

Controlled Substances Act at Walgreens stores, including fraudulent

prescriptions and the dispensing of controlled substances to customers without a

prescription, according to the U.S. attorney’s office in Colorado.

Employee theft

Walgreens eventually stopped the internal distribution of oxycodone and

hydrocodone, although the company continued to purchase controlled substances

from outside suppliers. The chain also removed sales of opioids from its bonus

calculations for pharmacists, according to court records.

The company declined to explain the change, but said dispensing volume was “one

of many factors” used to determine bonuses. “The nominal compensation factor in

question in no way incentivized pharmacists to inappropriately fill

prescriptions for any medication,” Walgreens said.

Although Walgreens had imposed limits on the number of opioid pills pharmacies

could order, stores could submit override requests if they needed more.

During 2014 and 2015, the company approved more than 95 percent of these

override requests from stores for controlled substances — totaling thousands of

orders — and boosted its overall sales of oxycodone, according to an internal

presentation filed in court.

As the pain pills kept flowing, so did problems with diversion. In 2015,

Walgreens reported to the DEA that nearly 2 million doses of controlled

substances were stolen or lost — a 16 percent increase from the previous year,

documents filed in court show.

Employee theft accounted for the largest share of missing pills, nearly

one-third, followed by armed robberies and “unexplained loss,” the documents

say. Pills containing oxycodone and hydrocodone topped the list.

Walgreens’s business practices have drawn scrutiny from state regulators, as

well. The boards that license the individual stores and pharmacists have

documented problems at company stores such as inadequate security, delays in

reporting thefts, inaccurate audits of controlled substances and insufficient

vetting of employees.

In Missouri, Walgreens employees allegedly have pilfered at least 138,000 pills

containing hydrocodone and oxycodone from 19 stores since 2005, according to

state board records. One of these cases involved a pharmacy technician at

Walgreens who stole about 7,500 pain pills in summer 2016 and told investigators

that she knew “how easy it would be” to take handfuls of pills and evade

security cameras.

The Post examined 67 investigations in 12 states in which pharmacy boards

censured Walgreens or placed pharmacies on probation for violating state

regulations, including inadequate security and theft of drugs. In some

instances, the company had to pay fines.

In July, Walgreens agreed to pay a $335,000 fine after the California State

Board of Pharmacy discovered that the company had allowed a woman without a

pharmacy degree or license to dispense prescriptions for over a decade.

The employee, Kim Thien Le, had worked at Walgreens since 1999, rising from

pharmacy cashier to pharmacy manager in 2016. She used the license numbers of

other pharmacists to dispense 745,355 prescriptions at 395 pharmacies, including

some remotely. In all, Le filled more than 100,000 prescriptions for controlled

substances, such as oxycodone, hydrocodone and fentanyl, according to state

records.

Le, who was charged this summer with three felonies alleging she falsely

impersonated licensed pharmacists, has a court date in January. An attorney

representing Le declined to comment.

The fine paid by Walgreens is one of the largest in the board’s history.

Walgreens declined to answer questions about Le and other enforcement actions.

“We take great pride in the judgment and patient care of our 28,000

pharmacists,” the company said. “In the event of a rare and isolated instance

when we learn of an employee acting improperly, we act swiftly to address the

matter and cooperate fully with law enforcement.”

Article originally published by

The Washington Post