The Brookings Institute Research Report

Released April 3, 2023,

Updated April 7th., 2023

Property Crimes - The Leading Driver of Urban America's Crime Surge - Up 34.7%

Between 2019 and 2022 in the four city research.

'The geography of crime in four U.S. cities: Perceptions and reality'

New York, Chicago, Seattle,

and Philadelphia.

Small business owners and major retailers alike

described increased property crime downtown as a major barrier to keeping their

business open.

Citywide crime increased between 2019 and 2022, driven primarily by property

crimes—but downtowns accounted for a very small share of these increases.

&uuid=(email))

Faced with slow-recovering

urban cores and

predictions of an “urban doom loop,”

many pundits and urban observers are returning to a

playbook not fully deployed since the 1990s—pointing

to public safety as the primary cause of a host of complex and interconnected

issues, from

office closures to

public transit budget shortfalls

to the broader decline of center cities.

Whether

or not crime

actually is up in central city business districts,

widespread fear of

crime—driven in no small part by relentless

media coverage—certainly is.

This is forcing urban leaders to simultaneously confront rising public safety

concerns while grappling with the numerous economic, social, and civic

aftershocks of an

enormously disruptive three

years. Unfortunately,

many of these aftershocks—such

as emptier streets and vacant storefronts—are the very same issues that

negatively impact perceptions of safety in the first place.

As local leaders seek to rebuild safe and vibrant downtowns, they must do so

without letting the perceptions and politics of crime drive policy and practice.

This research brief aims to equip leaders with the evidence to do just that by:

1) presenting findings from

nearly 100 interviews in four large U.S. cities (New York, Chicago, Seattle, and

Philadelphia) on perceptions of crime; 2) providing spatial analysis of the

geography of crime within these four cities; and 3) offering place-specific,

forward-looking policy and practice solutions to chart a future in which all

residents can feel—and actually be—safe regardless of where they live and work.

Brookings Metro’s

Future of Downtowns project: This report is part of a

larger mixed-methods research project

that seeks to understand

the future of American urban

cores through

interviews, spatial data analysis, and direct engagement with local leaders in

New York, Chicago, Seattle,

and Philadelphia.

Perceptions

of rising crime are impacting downtown recovery

When we began

qualitative interviews for this project in the fall of 2022, we expected to hear

comments mirroring

the think pieces of the day—something like, “The office is dead and

downtowns are being held back by workers’ growing desire for flexible, remote

work.” What we found instead is that residents and public and private sector

leaders overwhelmingly pointed to another challenge they believed was preventing

the recovery of center cities: fear of rising crime and a general sense of

“disorder” compromising previously “safe” areas of their cities. Five key themes

emerged from these conversations:

1. Respondents

overwhelmingly pointed to crime—not the desire for flexible work arrangements—as

the top barrier preventing workers’ return to office.

Across all four cities, the vast majority of residents, major employers,

property owners, small business owners, and other stakeholders reported rising

rates of violent crime and property crime downtown and indicators of “disorder”

(such as public drug use) as the top barriers stopping workers from coming back

to the office—and thus impeding downtown recovery.

|

“Safety,

security, substance use, and mental health—just the experience in public

areas—are the number-one issues preventing return-to-office.” — Seattle |

In New York and Philadelphia, in particular, respondents cited several recent

high-profile incidents of violence that occurred downtown as exacerbating

factors (which, in New York, also may have been influenced by

exponential increases in media coverage of crime in tourist hubs and subway

stations). In both

cities, such incidents can become

conflated in the media as an

inherent aspect of the

“urban doom loop” threatening city recovery.

|

“People

are scared. They’re afraid to walk on the streets. A woman on the first day

of [return-to-office] got punched to the ground on the way to work across

the street from our campus.” — Philadelphia |

2. Respondents also reported unsafe conditions on public transit as preventing

workers and visitors from commuting downtown.

Almost as often as stakeholders cited crime and a sense of disorder in downtowns

as barriers to returning to the office, they described safety issues on public

transit as hindering downtown commutes.

3.

Small business owners and major retailers alike described

increased property crime downtown as a major barrier to keeping their business

open. From small

mom-and-pops to major retailers, business owners reported higher costs for

private security, reduced foot traffic, and increased theft as significant

barriers to remaining open.

|

“There’s no question: The crime that’s gone up in this neighborhood is

burglary, larceny. It’s all stealing. You can’t buy half-and-half anymore,

it’s locked. You have to get an assistant to get half-and-half. Everything’s

locked up.” — New York City |

In many cases, stakeholders reported that this created a negative feedback loop

in which businesses closed due to safety concerns for their workers, reducing

foot traffic further and contributing to a greater sense of fear downtown.

|

“A lot

of the stores have closed because they’re in places where people were

congregating in ways that made other people feel unsafe. And so, they lost

their customers and reopening is hugely burdensome because you can’t get

anyone to come in because they don’t feel safe on that part of the

sidewalk…If it’s a block that no one feels safe in, you can’t fix that.” —

Seattle |

4. Residents and business owners in each city’s Chinatown neighborhood reported

greater safety concerns than other downtown stakeholders—driven primarily by

anti-Asian racism.

Stakeholders who lived or operated a business in the Chinatown neighborhood of

all four cities reported qualitatively different safety concerns than other

downtown stakeholders. In addition to reporting fears of theft and burglary,

they also cited concerns of anti-Asian racism and hate that increased during the

pandemic—causing many business owners to question whether to remain within their

districts and making safety a top concern for Asian residents in all four

cities.

|

“If you

ask anyone in Chinatown what their top three issues are, safety would be the

first one.” — Chicago |

5. Respondents varied in their perceptions of the geographic distribution of

crime within their cities.

Respondents generally took a dichotomous approach to understanding where within

their cities crime occurs—often taking a “downtown versus neighborhoods” view of

public safety. Many in Chicago and Philadelphia, in particular, reported a

perception that crime and conflicts “from the neighborhoods” were expanding into

downtown and exacerbating safety issues there. This perception fueled fear among

office workers who had previously seen downtown as relatively safe compared to

other neighborhoods.

|

“When

we had violence before, it was like, ‘Well, it’s over in that

neighborhood. It’s over in that neighborhood.’ And now folks feel

like it’s everywhere. ‘It doesn’t matter where I am, something could

happen to me.’” — Philadelphia |

In contrast, other stakeholders perceived that the attention paid to crime

downtown came at the expense of addressing long-standing neighborhood safety

concerns.

|

“If

we’re looking at Black and brown communities, they’re not represented in the

downtown area. In downtown, we’re looking at affluent communities with

higher economic statuses. The focus on [downtown crime] is sensationalized

because when something happens in Times Square, there is proximity to the

more affluent individuals.” — New York City |

&uuid=(email))

The mismatch

between perception and realities of crime: New spatial analysis

After completing our interviews, we compared those perceptions with both

national and neighborhood crime trends. Hyperlocal crime data reveals a

significant mismatch between residents’ perceived understanding of where crime

occurs in their city versus its actual spatial distribution. Several themes

emerged from our research, which have significant implications for policy and

practice.

National and

citywide trends only tell one piece of a larger story about violent crime—but

can have an outsized impact.

Respondents’ overall perceptions of rising crime were not wholly unfounded, but

they tended to reflect national and citywide crime rhetoric and sensationalized

media coverage rather than an understanding of where and how crime

actually occurs within their cities.

For instance, the national murder rate increased by nearly 30% between 2019 and

2020, driven predominantly by gun murders (Table 1). Cities and towns of all

sizes

saw their murder rates increase as well, rising over 35% in cities with

populations over 250,000; 40% percent in cities with populations of 100,000 to

250,000; and around 25% in cities with populations under 25,000. At the end of

2022,

analysis from the Council on Criminal Justice found that the national murder

rate was 34% higher than it was in 2019, but half of its historic peak in 1991.

But after looking more granularly at this pandemic-era increase in murders

within cities, it becomes clear that its toll was not distributed evenly.

Instead, increases in homicides were

largely concentrated in disadvantaged neighborhoods that already had high

rates of gun violence, along with significant histories of public and private

sector disinvestment.

This spatial concentration of pandemic-era homicides in disinvested

neighborhoods took place in all 16 cities in which it has been studied,

including

three of our four study cities: Chicago, Philadelphia, and Seattle.

Local data on

property and violent crimes shows that in New York, Philadelphia, and Chicago,

downtowns are some of the safest places to be.

Interview respondents were not only afraid of violence downtown.

They also spoke to a significant perceived increase in property crimes such as

retail theft, motor vehicle thefts, and robberies. Nationally,

evidence would seem to bear this out, as robberies increased by 5.5%,

nonresidential burglaries by 11%, larcenies by 8%, and motor vehicle thefts by

21% nationwide between 2021 and 2022.

However, when we looked at hyperlocal data, we identified three primary findings

related to property and violent crime downtown that defied these larger trends:

Citywide crime increased between 2019 and

2022, driven primarily by property crimes—but downtowns accounted for a very

small share of these increases.

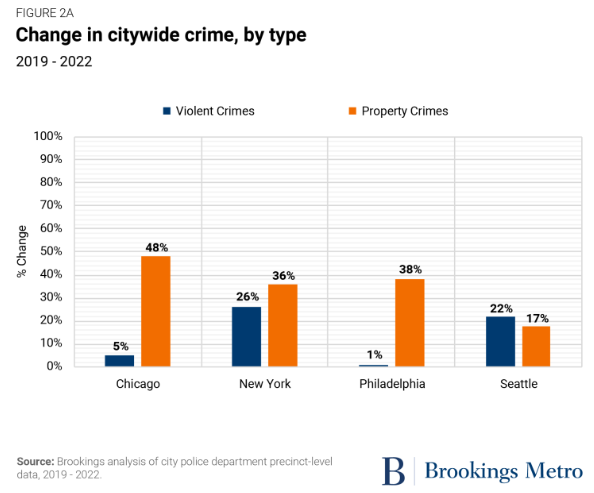

As shown in Figure 2a, between 2019 and 2022, there was a 48% increase in

property crimes in Chicago; a 38% increase in Philadelphia; a 36% increase

in New York; and a 17% increase in Seattle. For violent crime, there was a

5% increase in Chicago; 1% increase in Philadelphia; 26% increase in New

York; and a 22% increase in Seattle. |

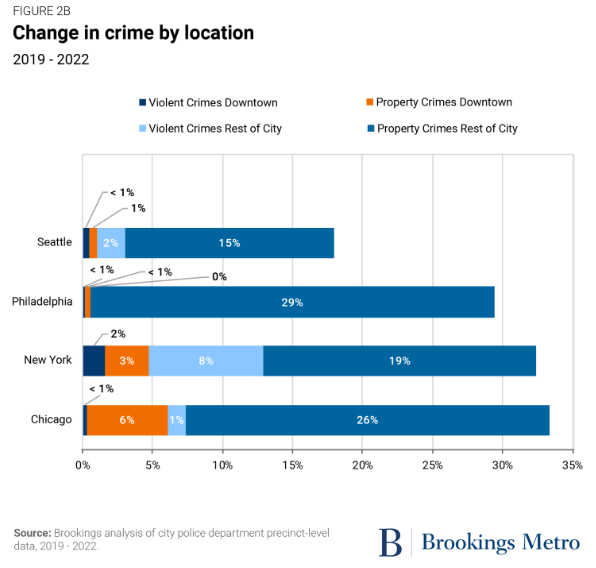

However, as shown in Figure 2b, downtown Chicago accounted for just 6% of the

citywide increase in property crime and less than 1% of the citywide increase in

violent crime. Manhattan’s core drove 3% of the citywide increase in property

crime and 2% of the increase in violent crime. Downtown Seattle accounted for

less than 1% of the city’s increase in violent crime and 1% of the increase in

property crime. And Center City Philadelphia accounted for less than 1% of the

increase in both categories.

The share of all crimes happening downtown

remained stable between 2019 and 2022

—and in a few cases declined.

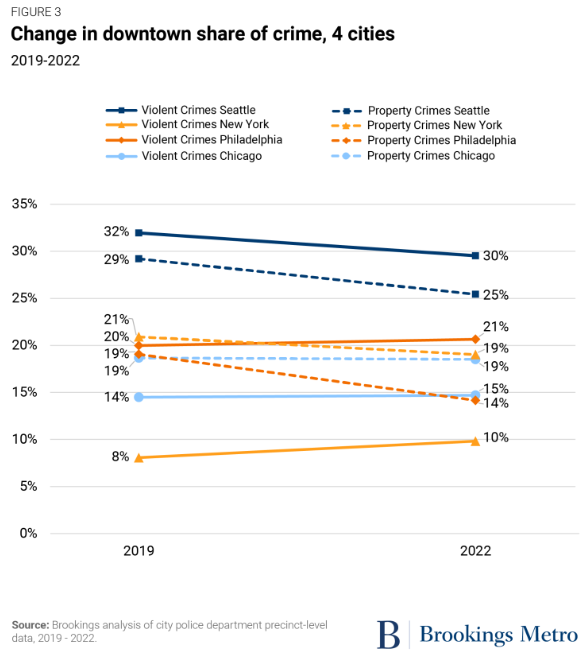

Another way to understand how crime may impact downtown recovery is to identify

whether the share of citywide crimes occurring downtown increased during the

pandemic. As Figure 3 demonstrates, our analysis found that across cities, the

share of crimes that occur downtown has remained relatively stable since the

onset of the pandemic, and actually declined in Seattle (for both property and

violent crime), New York (property crime only), and Philadelphia (property crime

only). That being said, there is wide variation across cohort cities in the

share of crimes that occur downtown, with Seattle (despite declines) seeing the

greatest share of both violent and property crimes occurring in its downtown.

While the share of violent crimes occurring

downtowns remained stable, small increases from a low baseline can seem more

significant than they are.

Mirroring nationwide trends, the share of violent crimes that are homicides

increased significantly in all four cohort cities between 2019 and 2022—rising

44% in Philadelphia, 33% in Chicago, 11% in Seattle, and 9% in New York (Figure

4). As discussed above, the share of violent crimes taking place downtown

remained relatively stable in all four cohort cities between 2019 and 2022

(Figure 3). In 2019, for example, the share of Seattle’s violent crime occurring

downtown was 32%; in 2022, it decreased to 30%. In New York, it went from 8% to

10% during the same period.

Importantly, however, even small changes in the relative share of violent crimes

that occur downtown may have an outsized impact on perception. In New York, for

instance, the 2% increase in the absolute share of violent crimes that occurred

downtown represents a 22% change in the relative share of violent crime

occurring downtown (Figure 4). New York’s downtown is still one of the safest

places to be in the city (and has the lowest share of violent crime of all four

downtowns studied), but its increase from such a low baseline (8% of all

citywide violent crime) and

extensive media coverage may be having an impact on perception.

Why the geography of crime matters

People deserve to feel—and actually be—safe regardless of where they live and

work. Downtowns have experienced significant disruptions since the pandemic that

have made workers, visitors, and residents feel uneasy. In particular, our

interviews revealed that increased visibility of public drug use, high-profile

violent crimes, vacant storefronts, emptier streets, and harassment are making

residents feel as though their city is in disarray, and that the government

isn’t doing much about it.

Pointing to the mismatch between where crime predominantly clusters and

residents’ perceptions is not designed to delegitimize their concerns or deny

the impact that crime in other parts of the city can have on perceptions of

downtown. Rather, it is to demonstrate that the spatial distribution of crime

has real implications for how local leaders can address it.

&uuid=(email)) For

instance, an extensive body of evidence demonstrates that

targeting investment and interventions in higher-crime communities—in

partnership and consultation with residents who actually live in those

communities—is one of the most effective solutions for combatting violence. Yet,

the voices of those most impacted by violence can be drowned out when the media,

politicians, and the public are hyper-focused on crime downtown.

For

instance, an extensive body of evidence demonstrates that

targeting investment and interventions in higher-crime communities—in

partnership and consultation with residents who actually live in those

communities—is one of the most effective solutions for combatting violence. Yet,

the voices of those most impacted by violence can be drowned out when the media,

politicians, and the public are hyper-focused on crime downtown.

Moreover, a laser focus on addressing crime downtown or preventing crime from

“spilling over” from the neighborhoods into downtown glosses over the

shared fate of downtowns and neighborhoods, and the

evidence on what works to promote safety for all residents of a city.

In short, perceptions matter because everyone should be able to feel safe, but

also because perceptions can drive policy in a way that can inadvertently make

residents less safe.

Toward a shared vision of safety, rooted in data

and evidence

When perceptions of crime are misaligned with evidence, local leaders may feel

pressure to pursue public safety solutions that are also not supported by

evidence—at a significant cost to their constituents.

Rather than allowing perceptions alone to drive decisionmaking, local leaders

can—and should—respond to rising fears of crime with evidence-based policies

that match where, why, and how crime actually occurs within cities. This does

not preclude providing reassurance to a society that has weathered an incredibly

turbulent past three years, and in fact can serve a dual purpose of doing just

that.

Below, we highlight key recommendations for improving safety and perceptions of

safety downtown, with a particular focus on forward-looking investments.

Notably, there are many other

evidence-based practices that can promote safety tailored for higher-crime

neighborhoods (some of which are covered here, but not all).

1.

Enhance alternative crisis response models for mental and behavioral health

emergencies. In most

cities and downtowns, police are the default responders for behavioral and

mental health crises, which

takes time and resources away from their ability to address other more

pressing public safety concerns such as violent crime. A

growing body of research demonstrates that alternative crisis response

models—which send trained, non-police mental health professionals to respond to

911 calls related to homelessness, substance use, and mental health—are both

more treatment-effective and cost-effective than traditional police responses.

Denver’s Support

Team Assisted Response (STAR), which has contributed to a 34%

drop in low-level crime, with visible results in

the downtown area. Seattle

and New

York are also taking strides to adopt and build out alternative crisis

response programs.

2. Invest in the

built environment.

Investments in the built environment—such as revitalizing

vacant lots,

painting

sidewalks, and

increasing greenery and

street lighting—have been found to significantly reduce crime, and property

crime in particular. I

3. Improve transit

safety with innovative strategies

4. Address the

intersection between economic security, employment, and safety.

Research points to a promising body of interventions aimed at enhancing safety

through economic opportunity. The most effective long-term solution is

decreasing unemployment—much of the reduction in property crime seen during

the 1990s can be attributed to the declining unemployment rate.

5. Strengthen

placemaking and place governance.

Residents’ feelings of

social cohesion and belonging in a neighborhood are also associated with

lower violent crime rates. Research has found that

increasing the number of spaces for informal contact between neighbors

(e.g., “third

places”) and investing in

creative placemaking can enhance residents’ sense of safety in urban areas.

Conclusion

Public, private, and civic sector leaders have the evidence and tools at their

disposal to advance pragmatic solutions that can not only improve perceptions of

safety, but also chart a future for cities in which all residents can actually

be safe, regardless of their ZIP code.

Understanding the geography of crime within cities is crucial because safety

solutions are not universal—what works to reduce certain crimes downtown may not

work in other areas suffering from generations of disinvestment and segregation.

The future of urban economies rests in

shared prosperity between downtown, neighborhoods, and their broader

regions. The same is true for safety—all residents of a region deserve to feel

and be safe, so leaders must deploy investments and interventions in a manner

that is most effective and humane in achieving that goal.

brookings.edu